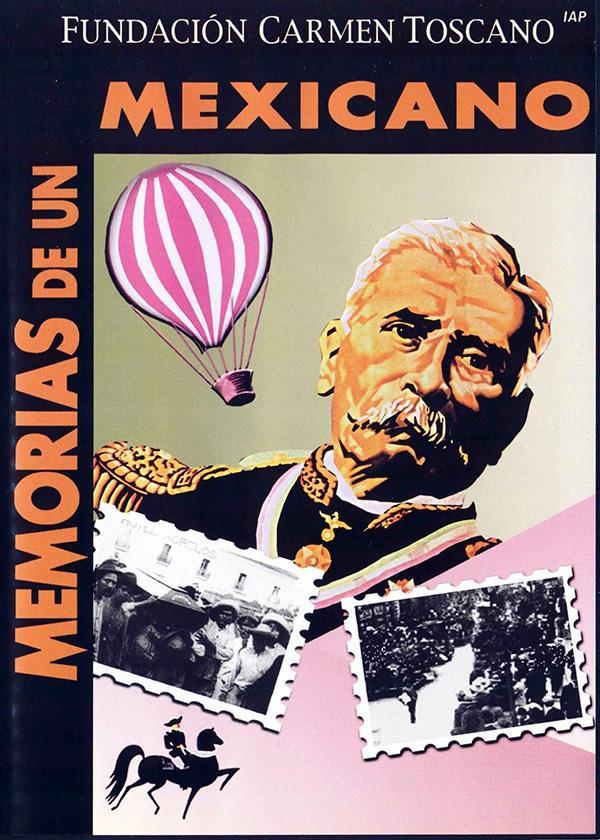

Memories of a Mexican; An Historic National Monument

| |

|

Few cinematographic works can succinctly relate, in just a few hours, fifty years of national history. Memorias de un mexicano/Memories of a Mexican (Carmen Toscano, 1950) is probably the best example of a film that, through documentary images, reconstructs half a century of a country's past.

"The best Mexican film"

In 1950, one of the greatest films in the history of Mexican cinema (the adjective refers both to its artistic magnificence and the all-encompassing nature of its story), Memoirs of a Mexican, was presented in what was a true media phenomenon at the time. At the premiere, artists, politicians and intellectuals alike gathered: José Vasconcelos, Vicente Lombardo Toledano, Luis Cabrera, Diego Rivera, Salvador Azuela, among other personalities, witnessed before anyone else what, in the words of writer José Alvarado Santos, was "the best Mexican film" that had been made up to that time.

Pioneer of the cinema

But what is it that makes this work exceptional? The answer lies in the dawn of Mexican filmmaking and in the generational change of a family of filmmakers. Memories of a Mexican is the result of more than thirty years of documentary memory and the participation of Salvador Toscano and his daughter Carmen.

Salvador Toscano was one of the first Mexicans to obtain a concession to use the Lumière brothers' cinematograph. His acquisition took place in 1897, only one year after this invention was presented in our country. From that date on, Toscano dedicated his life to the so-called seventh art and to the filming of documentary images from all over Mexico. Thanks to this work, one of the most important film archives in the nation was created, which would later bear his name.

Toscano's legacy includes fundamental images that have helped shape our imagery of the Mexican past, especially the Revolution. Particularly important are his films on the Maderista uprising of 1910 and the disturbances that preceded the resignation of President Porfirio Díaz, as well as those documenting the participation of the main protagonists of that historical period. Parallel to this, many other of his works constitute excellent documents of the daily life of our nation.

Carmen Toscano

Memorias de un mexicano obtained its raw material from Salvador Toscano's archive, which included newsreels and recordings by other cameramen; however, we cannot consider it a simple documentary exercise. Since 1942, writer Carmen Toscano had begun cataloguing her father's film materials. In the midst of that titanic task, she, accustomed to telling stories and writing poetry, devised what would become the most ambitious national film ever made. Her goal was to have 20th century Mexico as the protagonist and her choice was to weave the fictional account of a citizen who had witnessed the era.

Although Memorias de un mexicano focuses largely on the last years of the Porfiriato and the entire process of the Revolution, the story is told as a flashback with a voice that narrates from 1950 and recalls all the events that shaped Mexico during the twentieth century. Throughout the film, not only political personalities parade, but also customs, costumes, songs, parties and even buildings, all tangible indicators of the passage of time and the advance of modernity. In a certain sense, the film is similar to Diego Rivera's murals, in which many periods and people are portrayed in the same space (time, in the case of the film), besides the fact that it presents a version of history very much in tune with the nationalism and imagery of the time.

To give unity and coherence to the images of so many years, Carmen Toscano decided to include a first-person voice-over narration that narrates the events. The voice chosen to tell the story was that of one of the most brilliant Mexican radio broadcasters of the time: Manuel Bernal, better known as the Declamador de América.

Jorge Pérez Herrera was in charge of setting the music for the film. He selected the pieces that illustrate the different periods shown in the film, including corridos about Francisco I. Madero, Emiliano Zapata, Francisco Villa, Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón. Memorias de un mexicano is, therefore, not only an important visual catalog of our past, but also a sound document that recovers some of the popular Mexican songs of the first half of the 20th century.

Cinema, memory and heritage

If the artistic recognition was immediate, the valuation of its historical importance occurred seventeen years later: in 1967 the National Institute of Anthropology and History confirmed the exceptional essence of Memoirs of a Mexican by declaring it a Historic Monument of the country. Interviewed that year by Elena Poniatowska, after the film obtained the distinction, Carmen Toscano highlighted her creative work, but at the same time ratified the patrimonial characteristics of the film:

"Let's suppose that a pyramid is discovered on my land; that pyramid belongs to the nation, even though the land is mine. In the case of the film it is the same. The film is mine, but the images belong to the nation."

Such is the valuable legacy of Memoirs of a Mexican.

|

| poster taken from filmaffinity.com |

If you wish to read the full article, please purchase the issue #120 in print or digital format: Guillermo Prieto. (Print version.) Guillermo Prieto. (Digital version.)

This post comes from http://fucofilms.com/blog/2022/08/17/memorias-de-un-mexicano-monumento-historico-de-la-nacion/ Originally published in Spanish and and translated with a little help of DeepL.com/Translator (Sourse: ¿POR QUÉ “MEMORIAS DE UN MEXICANO” ES LA ÚNICA PELÍCULA QUE HA SIDO DECLARADA MONUMENTO HISTÓRICO DE LA NACIÓN? Relatos e Historias en México. 15 de agosto de 2018 ©EDITORIAL RAÍCES, S.A. DE C.V. .)

Comments

Post a Comment